6. Oncogenes

Marco A. Pierotti, PhD

Gabriella Sozzi, PhD

Carlo M. Croce, MD

Since the early proposals of Boveri more than a century ago, much

experimental evidence has confirmed that, at the molecular level, cancer is a

result of lesions in the cellular deoxyribonucleic acid (DN)A.

First, it has been observed that a cancer cell transmits to its daughter cells

the phenotypic features characterizing the cancerous state. Second, most of the

recognized mutagenic compounds are also carcinogenic, having as a target

cellular DNA. Finally, the karyotyping of several types of human tumors,

particularly those belonging to the hematopoietic system, led to the

identification of recurrent qualitative and numerical chromosomal aberrations,

reflecting pathologic re-arrangements of the cellular genome. Taken together,

these observations suggest that the molecular pathogenesis of human cancer is

due to structural and/or functional alterations of specific genes whose normal

function is to control cellular growth and differentiation or, in different

terms, cell birth and cell death.1,2

The identification and characterization of the genetic elements playing a

role in the scenario of human cancer pathogenesis have been made possible by

the development of DNA recombinant techniques during the last two decades. One

milestone was the use of the DNA transfection technique that helped clarify the

cellular origin of the “viral oncogenes.” The latter were previously

characterized as the specific genetic elements capable of conferring the

tumorigenic properties to the ribonucleic acid (RNA) tumor viruses also known

as retroviruses.3,4 Furthermore, the transfection technique led to the

identification of cellular transforming genes that do not have a viral

counterpart. Besides the source of their original identification, viral or

cellular genome, these transforming genetic elements have been designated as

protooncogenes in their normal physiologic version and oncogenes when altered

in cancer.5,6 A second relevant experimental approach

has regarded the identification and characterization of clonal and recurrent

cytogenetic abnormalities in cancer cells, especially those derived from the

hematopoietic system. Several oncogenes have been thus defined by molecular

cloning of the chromosomal breakpoints, including translocations and

inversions. Additional oncogenes have been identified through the analysis of

chromosomal regions anomalously stained (homogeneously staining regions),

representing gene amplification. Finally, the detection of chromosome deletions

has been instrumental in the process of identification and cloning of a second

class of cancer-associated genes, the tumor suppressors. Contrary to the

oncogenes that are activated by dominant mutations and whose activity is to

promote cell growth, tumor suppressors act in the normal cell as negative

controllers of cell growth and are inactive in tumor cells. In general,

therefore, the mutations inactivating tumor suppressor genes are of the

recessive type.7

Recently, a third class of cancer-associated genes has been defined

thanks to the analysis of tumors of a particular type; that is, tumors in which

an inherited mutated predisposing gene plays a significant role. These tumors

include cancers in patients suffering from hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal

cancer syndromes.

The genes implicated in these tumors have been defined as mutator genes

or genes involved in the DNA-mismatch repair process. Although not directly

involved in the carcinogenesis process, these genes, when inactivated, expose

the cells to a very high mutagenic load that eventually may involve the

activation of oncogenes and the inactivation of tumor suppressors.8

In this chapter, the methods by which oncogenes were discovered will be

first described. The various functions of cellular protooncogenes will then be

presented, and the genetic mechanisms of protooncogene activation will be

summarized. Finally, the role of specific oncogenes in the initiation and

progression of human tumors will be discussed.

Discovery and identification

of oncogenes

The first oncogenes were discovered through the study of retroviruses,

RNA tumor viruses whose genomes are reverse-transcribed into DNA in infected

animal cells.9 During the course of infection,

retroviral DNA is inserted into the chromosomes of host cells. The integrated

retroviral DNA, called the provirus, replicates along with the cellular DNA of

the host.10 Transcription of the DNA provirus leads to the production of viral

progeny that bud through the host cell membrane to infect other cells. Two

categories of retroviruses are classified by their time course of tumor

formation in experimental animals. Acutely transforming retroviruses can

rapidly cause tumors within days after injection. These retroviruses can also

transform cell cultures to the neoplastic phenotype. Chronic or weakly

oncogenic retroviruses can cause tissue-specific tumors in susceptible strains

of experimental animals after a latency period of many months. Although weakly

oncogenic retroviruses can replicate in vitro, these viruses do not transform

cells in culture.

Retroviral oncogenes are altered versions of host cellular protooncogenes

that have been incorporated into the retroviral genome by recombination with

host DNA, a process known as retroviral transduction.11 This surprising

discovery was made through study of the Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) (Figure 6-1).

RSV is an acutely transforming retrovirus first isolated from a chicken sarcoma

over 80 years ago by Peyton Rous.12 Studies of RSV mutants in the early 1970s

revealed that the transforming gene of RSV was not required for viral

replication.13–15 Molecular hybridization studies then showed that the RSV

transforming gene (designated v-src) was homologous to a host cellular gene

(c-src) that was widely conserved in eukaryotic species.16 Studies of many

other acutely transforming retroviruses from fowl, rodent, feline, and nonhuman

primate species have led to the discovery of dozens of different retroviral

oncogenes (see below and Table 6-1). In every case, these retroviral oncogenes

are derived from normal cellular genes captured from the genome of the host.

Viral oncogenes are responsible for the rapid tumor formation and efficient in

vitro transformation activity characteristic of acutely transforming retroviruses.

In contrast to acutely transforming retroviruses, weakly oncogenic

retroviruses do not carry viral oncogenes. These retroviruses, which include

mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) and various animal leukemia viruses, induce

tumors by a process called insertional mutagenesis (Figure 6-2).8 This process results from integration of the DNA provirus

into the host genome in infected cells. In rare cells, the provirus inserts

near a protooncogene. Expression of the protooncogene is then abnormally driven

by the transcriptional regulatory elements contained within the long terminal

repeats of the provirus.17,18 In these cases, proviral

integration represents a mutagenic event that activates a protooncogene.

Activation of the protooncogene then results in transformation of the cell,

which can grow clonally into a tumor. The long latent period of tumor formation

of weakly oncogenic retroviruses is therefore due to the rarity of the provirus

insertional event that leads to tumor development from a single transformed cell.

Insertional mutagenesis by weakly oncogenic retroviruses, first demonstrated in

bursal lymphomas of chickens, frequently involves the same oncogenes (such as

myc, myb, and erb B) that are carried by acutely transforming

retroviruses.19–21 In many cases, however, insertional mutagenesis has been

used as a tool to identify new oncogenes, including int-1, int-2, pim-1, and

lck.22

The demonstration of activated protooncogenes in human tumors was first

shown by the DNA-mediated transformation technique.23,24 This technique, also

called gene transfer or transfection assay, verifies the ability of donor DNA

from a tumor to transform a recipient strain of rodent cells called NIH 3T3, an

immortalized mouse cell line (Figure 6-3).25,26 This sensitive assay, which can

detect the presence of single-copy oncogenes in a tumor sample, also enables

the isolation of the transforming oncogene by molecular cloning techniques.

After serial growth of the transformed NIH 3T3 cells, the human tumor oncogene

can be cloned by its association with human repetitive DNA sequences. The first

human oncogene isolated by the gene transfer technique was derived from a

bladder carcinoma.27,28 Overall, approximately 20% of

individual human tumors have been shown to induce transformation of NIH 3T3

cells in gene-transfer assays. The value of transfection assay was recently

reinforced by the laboratory of Robert Weinberg, which showed that the ectopic

expression of the telomerase catalytic subunit (hTERT), in combination with the

simian virus 40 large T product and a mutated oncogenic H-ras protein, resulted

in the direct tumorigenic conversion of normal human epithelial and fibroblast

cells.29 Many of the oncogenes identified by gene-transfer studies are

identical or closely related to those oncogenes transduced by retroviruses.

Most prominent among these are members of the ras family that have been

repeatedly isolated from various human tumors by gene transfer.30,31 A number

of new oncogenes (such as neu, met, and trk) have also been identified by the

gene-transfer technique.32,33 In many cases, however, oncogenes identified by

gene transfer were shown to be activated by rearrangement during the

experimental procedure and are not activated in the human tumors that served as

the source of the donor DNA, as in the case of ret that was subsequently found

genuinely rearranged and activated in papillary thyroid carcinomas.34–36

Chromosomal translocations have served as guideposts for the discovery of

many new oncogenes.37,38 Consistently recurring

karyotypic abnormalities are found in many hematologic and solid tumors. These

abnormalities include chromosomal rearrangements as well as the gain or loss of

whole chromosomes or chromosome segments. The first consistent karyotypic

abnormality identified in a human neoplasm was a characteristic small

chromosome in the cells of patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia.39 Later

identified as a derivative of chromosome 22, this abnormality was designated

the

Oncogenes, protooncogenes,

and their functions

Protooncogenes encode proteins that are involved in the control of cell

growth. Alteration of the structure and/or expression of protooncogenes can

activate them to become oncogenes capable of inducing in susceptible cells the

neoplastic phenotype. Oncogenes can be classified into five groups based on the

functional and biochemical properties of protein products of their normal

counterparts (proto-oncogenes). These groups are (1) growth factors, (2) growth

factor receptors, (3) signal transducers, (4) transcription factors, and (5)

others, including programmed cell death regulators. Table 6-1 lists examples of

oncogenes according to their functional categories.

Growth Factors

Growth factors are secreted polypeptides that function as extracellular

signals to stimulate the proliferation of target cells.41,42

Appropriate target cells must possess a specific receptor in order to respond

to a specific type of growth factor. A well-characterized example is

platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), an approximately 30 kDa protein

consisting of two polypeptide chains.43 PDGF is released from

platelets during the process of blood coagulation. PDGF stimulates the

proliferation of fibroblasts, a cell growth process that plays an important

role in wound healing. Other well-characterized examples of growth factors

include nerve growth factor, epidermal growth factor, and fibroblast growth

factor.

The link between growth factors and retroviral oncogenes was revealed by

study of the sis oncogene of simian sarcoma virus, a retrovirus first isolated

from a monkey fibrosarcoma. Sequence analysis showed that sis encodes the beta

chain of PDGF.44 This discovery established the

principle that inappropriately expressed growth factors could function as

oncogenes. Experiments demonstrated that the constitutive expression of the sis

gene product (PDGF-β)

was sufficient to cause neoplastic transformation of fibroblasts but not of

cells that lacked the receptor for PDGF.45 Thus, transformation by sis requires

interaction of the sis gene product with the PDGF receptor. The mechanism by

which a growth factor affects the same cell that produces it is called

autocrine stimulation .46 The constitutive expression

of the sis gene product appears to cause neoplastic transformation by the

mechanism of autocrine stimulation, resulting in self-sustained aberrant cell

proliferation. This model, derived from experimental animal systems, has been

recently demonstrated in a human tumor. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DP) is

an infiltrative skin tumor that was demonstrated to present specific

cytogenetic features: reciprocal translocation and supernumerary ring

chromosomes, involving chromosomes 17 and 22.47,48 Molecular cloning of the

breakpoints revealed a fusion between the collagen type Ia1 (COL1A1) gene and

PDGF-β gene. The fusion gene

resulted in a deletion of PDGF-β exon 1 and a constitutive release of this growth factor.49 Subsequent

experiments of gene transfer of DPs genomic DNA into NIH 3T3 cells directly

demonstrated the occurrence of an autocrine mechanism by the human rearranged

PDGF-b gene involving the activation of the endogenous PDGF receptor.50,51 Another example of a growth factor that can function as

an oncogene is int-2, a member of the fibroblast growth factor family. Int-2 is

sometimes activated in mouse mammary carcinomas by MMTV insertional

mutagenesis.52top link

Growth Factor Receptors

Some viral oncogenes are altered versions of normal growth factor

receptors that possess intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity.53 Receptor tyrosine

kinases, as these growth factor receptors are collectively known,

have a characteristic protein structure consisting of three principal domains:

(1) the extracellular ligand-binding domain, (2) the transmembrane domain, and

(3) the intracellular tyrosine kinase catalytic domain (see Figure 6-2). Growth

factor receptors are molecular machines that transmit information in a

unidirectional fashion across the cell membrane. The binding of a growth factor

to the extracellular ligandbinding domain of the receptor results in the

activation of the intracellular tyrosine kinase catalytic domain. The

recruitment and phosphorylation of specific cytoplasmic proteins by the

activated receptor then trigger a series of biochemical events generally

leading to cell division.

Because of the role of growth factor receptors in the regulation of

normal cell growth, it is not surprising that these receptors constitute an

important class of protooncogenes. Examples include erb B, erb B-2, fms, kit,

met, ret, ros, and trk. Mutation or abnormal expression of growth factor

receptors can convert them into oncogenes.54 For example, deletion of the

ligand-binding domain of erb B (the epidermal growth factor receptor) is

thought to result in constitutive activation of the receptor in the absence of

ligand binding.55 Point mutation in the tyrosine kinase domain or of the

extracellular domain and deletion of intracellular regulatory domains can also

result in the constitutive activation of receptor tyrosine kinases. Increased

expression through gene amplification and abnormal expression in the wrong cell

type are additional mechanisms through which growth factor receptors may be

involved in neoplasia. The identification and study of altered growth factor

receptors in experimental models of neoplasia have contributed much to our

understanding of the normal regulation of cell proliferation.

Signal Transducers

Mitogenic signals are transmitted from growth factor receptors on the

cell surface to the cell nucleus through a series of complex interlocking

pathways collectively referred to as the signal transduction cascade.56 This relay of information is accomplished in part by the

stepwise phosphorylation of interacting proteins in the cytosol. Signal

transduction also involves guanine nucleotide-binding proteins and second

messengers such as the adenylate cyclase system.57 The

first retroviral oncogene discovered, src, was subsequently shown to be

involved in signal transduction.

Many protooncogenes are members of signal transduction pathways.58,59 These consist of two main groups: nonreceptor protein

kinases and guanosine triphosphate (GTP)-binding proteins. The nonreceptor

protein kinases are subclassified into tyrosine kinases (eg, abl, lck, and src)

and serine/threonine kinases (eg, raf-1, mos, and pim-1). GTP-binding proteins

with intrinsic GTPase activity are subdivided into monomeric and heterotrimeric

groups.60 Monomeric GTP-binding proteins are members of the important ras

family of protooncogenes that includes H-ras, K-ras, and N-ras.61

Heterotrimeric GTP-binding proteins (G proteins) implicated as protooncogenes

currently include gsp and gip. Signal transducers are often converted to

oncogenes by mutations that lead to their unregulated activity, which in turn

leads to uncontrolled cellular proliferation.62

Transcription Factors

Transcription factors are nuclear proteins that regulate the expression

of target genes or gene families.63 Transcriptional regulation is mediated by

protein binding to specific DNA sequences or DNA structural motifs, usually located

upstream of the target gene. Transcription factors often belong to multigene

families that share common DNA-binding domains such as zinc fingers. The

mechanism of action of transcription factors also involves binding to other

proteins, sometimes in heterodimeric complexes with specific partners.

Transcription factors are the final link in the signal transduction pathway

that converts extracellular signals into modulated changes in gene expression.

Many protooncogenes are transcription factors that were discovered

through their retroviral homologs.64 Examples include erb A, ets, fos, jun,

myb, and c-myc. Together, fos and jun form the AP-1 transcription factor, which

positively regulates a number of target genes whose expression leads to cell

division.65,66 Erb A is the receptor for the T3 thyroid hormone,

triiodothyronine.67 Protooncogenes that function as transcription factors are

often activated by chromosomal translocations in hematologic and solid

neoplasms.68 In certain types of sarcomas, chromosomal translocations cause the

formation of fusion proteins involving the association of EWS gene with various

partners and resulting in an aberrant tumor-associated transcriptional

activity. Interestingly, a role of the adenovirus E1A gene in promoting the

formation of fusion transcript fli1/ews in normal human fibroblasts was

recently reported.69 An important example of a protooncogene with a

transcriptional activity in human hematologic tumors is the c-myc gene, which

helps to control the expression of genes leading to cell proliferation.70 As

will be discussed later in this chapter, the cmyc gene is frequently activated

by chromosomal translocations in human leukemia and lymphoma.

Programmed Cell Death

Regulation

Normal tissues exhibit a regulated balance between cell proliferation and

cell death. Programmed cell death is an important component in the processes of

normal embryogenesis and organ development. A distinctive type of programmed

cell death, called apoptosis, has been described for mature tissues.71 This process is characterized morphologically by blebbing of

the plasma membrane, volume contraction, condensation of the cell nucleus, and

cleavage of genomic DNA by endogenous nucleases into nucleosome-sized

fragments. Apoptosis can be triggered in mature cells by external stimuli such

as steroids and radiation exposure. Studies of cancer cells have shown that

both uncontrolled cell proliferation and failure to undergo programmed cell

death can contribute to neoplasia and insensitivity to anticancer treatments.

The only protooncogene thus far shown to regulate programmed cell death

is bcl-2. Bcl-2 was discovered by the study of chromosomal translocations in

human lymphoma.72,73 Experimental studies show that bcl-2 activation inhibits

programmed cell death in lymphoid cell populations.74 The dominant mode of

action of activated bcl-2 classifies it as an oncogene. The bcl-2 gene encodes

a protein localized to the inner mitochondrial membrane, endoplasmic reticulum,

and nuclear membrane. The mechanism of action of the bcl-2 protein has not been

fully elucidated, but studies indicate that it functions in part as an

antioxidant that inhibits lipid peroxidation of cell membranes.75 The normal function of bcl-2 requires interaction with other

proteins, such as bax, also thought to be involved in the regulation of

programmed cell death (Figure 6-4). It is unlikely that bcl-2 is the only

apoptosis gene involved in neoplasia although additional protooncogenes await

identification.

Mechanisms of oncogene

activation

The activation of oncogenes involves genetic changes to cellular

protooncogenes. The consequence of these genetic alterations is to confer a

growth advantage to the cell. Three genetic mechanisms activate oncogenes in

human neoplasms: (1) mutation, (2) gene amplification, and (3) chromosome

rearrangements. These mechanisms result in either an alteration of

protooncogene structure or an increase in protooncogene expression (Figure

6-5). Because neoplasia is a multistep process, more than one of these mechanisms

often contribute to the genesis of human tumors by

altering a number of cancer-associated genes. Full expression of the neoplastic

phenotype, including the capacity for metastasis, usually involves a

combination of protooncogene activation and tumor suppressor gene loss or

inactivation.

Mutation

Mutations activate protooncogenes through structural alterations in their

encoded proteins. These alterations, which usually involve critical protein

regulatory regions, often lead to the uncontrolled, continuous activity of the

mutated protein. Various types of mutations, such as base substitutions,

deletions, and insertions, are capable of activating protooncogenes.76 Retroviral oncogenes, for example, often have deletions that

contribute to their activation. Examples include deletions in the aminoterminal

ligand-binding domains of the erb B, kit, ros, met, and trk oncogenes.6 In human tumors, however, most characterized oncogene

mutations are base substitutions (point mutations) that change a single amino

acid within the protein.

Point mutations are frequently detected in the ras family of

protooncogenes (K-ras, H-ras, and N-ras).77 It has been estimated that as many

as 15% to 20% of unselected human tumors may contain a ras mutation. Mutations

in K-ras predominate in carcinomas. Studies have found K-ras mutations in about

30% of lung adenocarcinomas, 50% of colon carcinomas, and 90% of carcinomas of

the pancreas.78 N-ras mutations are preferentially found in hematologic

malignancies, with up to a 25% incidence in acute myeloid leukemias and

myelodysplastic syndromes.79,80 The majority of thyroid carcinomas have been

found to have ras mutations distributed among K-ras, H-ras, and N-ras, without

preference for a single ras family member but showing an association with the

follicular type of differentiated thyroid carcinomas.81,82 The majority of ras

mutations involve codon 12 of the gene, with a smaller number involving other

regions such as codons 13 or 61.83 Ras mutations in human tumors have been

linked to carcinogen exposure. The consequence of ras mutations is the

constitutive activation of the signal-transducing function of the ras protein.

Another significant example of activating point mutations is represented

by those affecting the ret protooncogene in multiple endocrine neoplasia type

2A syndrome (MEN2A).

Germline point mutations affecting one of the cysteines located in the

juxtamembrane domain of the ret receptor have been found to confer an oncogenic

potential to the latter as a consequence of the ligand-independent activation

of the tyrosine kinase activity of the receptor. Experimental evidences have

pointed out that these mutations involving cysteine residues promote ret

homodimerization via the formation of intermolecular disulfide bonding, most

likely as a result of an unpaired number of cysteine residues.84,85

Gene Amplification

Gene amplification refers to the expansion in copy number of a gene

within the genome of a cell. Gene amplification was first discovered as a

mechanism by which some tumor cell lines can acquire resistance to

growth-inhibiting drugs.86 The process of gene amplification occurs through

redundant replication of genomic DNA, often giving rise to karyotypic

abnormalities called double-minute chromosomes (DMs) and homogeneous staining

regions (HSRs).87 DMs are characteristic minichromosome structures without

centromeres. HSRs are segments of chromosomes that lack the normal alternating

pattern of light- and dark-staining bands. Both DMs and HSRs represent large

regions of amplified genomic DNA containing up to several hundred copies of a

gene. Amplification leads to the increased expression of genes, which in turn

can confer a selective advantage for cell growth.

The frequent observation of DMs and HSRs in human tumors suggested that

the amplification of specific protooncogenes may be a common occurrence in

neoplasia.88 Studies then demonstrated that three protooncogene families-myc,

erb B, and ras-are amplified in a significant number of human tumors (Table

6-2). About 20% to 30% of breast and ovarian cancers show c-myc amplification,

and an approximately equal frequency of c-myc amplification is found in some

types of squamous cell carcinomas.89 N-myc was discovered as a new member of

the myc protooncogene family through its amplification in neuroblastomas.90

Amplification of N-myc correlates strongly with advanced tumor stage in

neuroblastoma (Table 6-3), suggesting a role for this gene in tumor

progression.91,92 L-myc was discovered through its amplification in small-cell

carcinoma of the lung, a neuroendocrine-derived tumor.93 Amplification of erb

B, the epidermal growth factor receptor, is found in up to 50% of glioblastomas

and in 10% to 20% of squamous carcinomas of the head and neck.77 Approximately

15% to 30% of breast and ovarian cancers have amplification of the erbB-2

(HER-2/neu) gene. In breast cancer, erbB-2 amplification correlates with

advanced stage and poor prognosis.94 Members of the ras gene family, including

K-ras and N-ras, are sporadically amplified in various carcinomas.

Chromosomal Rearrangements

Recurring chromosomal rearrangements are often detected in hematologic

malignancies as well as in some solid tumors.37,95,96 These rearrangements

consist mainly of chromosomal translocations and, less frequently, chromosomal

inversions. Chromosomal rearrangements can lead to hematologic malignancy via

two different mechanisms: (1) the transcriptional activation of protooncogenes

or (2) the creation of fusion genes. Transcriptional activation, sometimes

referred to as gene activation, results from chromosomal rearrangements that

move a proto-oncogene close to an immunoglobulin or T-cell receptor gene (see

Figure 6-5). Transcription of the protooncogene then falls under control of

regulatory elements from the immunoglobulin or T-cell receptor locus. This

circumstance causes deregulation of protooncogene expression, which can then

lead to neoplastic transformation of the cell.

Fusion genes can be created by chromosomal rearrangements when the

chromosomal breakpoints fall within the loci of two different genes. The

resultant juxtaposition of segments from two different genes gives rise to a

composite structure consisting of the head of one gene and the tail of another.

Fusion genes encode chimeric proteins with transforming activity. In general,

both genes involved in the fusion contribute to the transforming potential of

the chimeric oncoprotein. Mistakes in the physiologic rearrangement of

immunoglobulin or T-cell receptor genes are thought to give rise to many of the

recurring chromosomal rearrangements found in hematologic malignancy.97

Examples of molecularly characterized chromosomal rearrangements in hematologic

and solid malignancies are given in Table 6-4. In some cases, the same

protooncogene is involved in several different translocations (ie, c-myc, ews,

and ret).

Gene Activation

The t(8;14)(q24;q32) translocation, found in

about 85% of cases of Burkitt lymphoma, is a well-characterized example of the

transcriptional activation of a proto-oncogene. This chromosomal rearrangement

places the c-myc gene, located at chromosome band 8q24, under control of

regulatory elements from the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus located at

14q32.98 The resulting transcriptional activation of c-myc, which encodes a

nuclear protein involved in the regulation of cell proliferation, plays a

critical role in the development of Burkitt lymphoma.99 The c-myc gene is also

activated in some cases of Burkitt lymphoma by translocations involving

immunoglobulin light-chain genes.100,101 These are t(2;8)(p12;q24), involving

the κ locus located at 2p12, and t(8;22)(q24;q11), involving the κ

locus at 22q11 (Figure 6-6). Although the position of the chromosomal

breakpoints relative to the c-myc gene may vary considerably in individual

cases of Burkitt lymphoma, the consequence of the translocations is the same:

deregulation of c-myc expression, leading to uncontrolled cellular

proliferation.

In some cases of T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL), the c-myc

gene is activated by the t(8;14)(q24;q11)

translocation. In these cases, transcription of c-myc is placed under the

control of regulatory elements within the T-cell receptor α locus located

at 14q11.102 In addition to c-myc, several protooncogenes that encode nuclear

proteins are activated by various chromosomal translocations in T-ALL involving

the T-cell receptor α or β locus. These include HOX11, TAL1, TAL2,

and RBTN1/Tgt1.103–105 The proteins encoded by these

genes are thought to function as transcription factors through DNA-binding and

protein-protein interactions. Overexpression or inappropriate expression of

these proteins in T cells is thought to inhibit T-cell differentiation and lead

to uncontrolled cellular proliferation.

A number of other protooncogenes are also activated by chromosomal

translocations in leukemia and lymphoma. In most follicular lymphomas and some

large cell lymphomas, the bcl-2 gene (located at 18q21) is activated as a

consequence of t(14;18)(q32;q21) translocations.72,73 Overexpression of the

bcl-2 protein inhibits apoptosis, leading to an imbalance between lymphocyte

proliferation and programmed cell death.74 Mantle cell lymphomas are

characterized by the t(11;14)(q13;q32) translocation, which activates the

cyclin d1 (bcl-1) gene located at 11q13.106,107 Cyclin D1 is a G1 cyclin

involved in the normal regulation of the cell cycle. In some cases of T cell

chronic lymphocytic leukemia and prolymphocytic leukemia, the tcl-1 gene at

14q32.1 is activated by inversion or translocation involving chromosome 14.108 The tcl-1 gene product is a small cytoplasmic protein whose

function is not yet known.

Gene Fusion

The first example of gene fusion was discovered through the cloning of

the breakpoint of the Philadelphia chromosome in chronic myelogenous leukemia

(CML).109 The t(9;22)(q34;q11) translocation in CML fuses the c-abl gene,

normally located at 9q34, with the bcr gene at 22q11 (Figure 6-7).110 The

bcr/abl fusion, created on the der(22) chromosome, encodes a chimeric protein

of 210 kDa, with increased tyrosine kinase activity and abnormal cellular

localization.111 The precise mechanism by which the bcr/abl fusion protein

contributes to the expansion of the neoplastic myeloid clone is not yet known.

The t(9;22) translocation is also found in up to 20%

of cases of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). In these cases, the breakpoint

in the bcr gene differs somewhat from that found in CML, resulting in a 185 kDa

bcr/abl fusion protein.112 It is unclear at this time

why the slightly smaller bcr/abl fusion protein leads to such a large

difference in neoplastic phenotype.

In addition to c-abl, two other genes encoding tyrosine kinases are

involved in distinct gene fusion events in hematologic malignancy. The t(2;5)(p23;q35) translocation in anaplastic large cell

lymphomas fuses the NPM gene (5q35) with the ALK gene (2p23).113 ALK encodes a

membranespanning tyrosine kinase similar to members of the insulin growth

factor receptor family. The NPM protein is a nucleolar phosphoprotein involved

in ribosome assembly. The NPM/ALK fusion creates a chimeric oncoprotein in

which the ALK tyrosine kinase activity may be constitutively activated. The t(5;12)(q33;p13) translocation, characterized in a case of

chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, fuses the tel gene (12p13) with the tyrosine kinase

domain of the PDGF receptor b gene (PDGFR-b at 5q33).114 The tel gene is

thought to encode a nuclear DNA-binding protein similar to those of the ets

family of protooncogenes.

Gene fusions sometimes lead to the formation of chimeric transcription

factors.68,95 The t(1;19)(q23;p13) translocation,

found in childhood pre-B-cell ALL, fuses the E2A transcription factor gene

(19p13) with the PBX1 homeodomain gene (1q23).115 The E2A/PBX1 fusion protein

consists of the amino-terminal transactivation domain of the E2A protein and

the DNA-binding homeodomain of the PBX1 protein. The t(15;17)(q22;q21)

translocation in acute promyelocytic leukemia (PML) fuses the PML gene (15q22)

with the RARA gene at 17q21.116 The PML protein contains a zinc-binding domain

called a RING finger that may be involved in protein-protein interactions. RARA

encodes the retinoic acid alpha-receptor protein, a member of the nuclear

steroid/thyroid hormone receptor superfamily. Although retinoic acid binding is

retained in the fusion protein, the PML/RARA fusion protein may confer altered

DNA-binding specificity to the RARA ligand complex.117 Leukemia patients with

the PML/RARA gene fusion respond well to retinoid treatment. In these cases,

treatment with all-trans retinoic acid induces differentiation of PML cells.

The ALL1 gene, located at chromosome band 11q23, is involved in

approximately 5% to 10% of acute leukemia cases overall in children and

adults.118,119 These include cases of ALL, acute

myeloid leukemia, and leukemias of mixed cell lineage. Among leukemia genes,

ALL1 (also called MLL and HRX) is unique because it participates in fusions

with a large number of different partner genes on the various chromosomes. Over

20 different reciprocal translocations involving the ALL1 gene at 11q23 have

been reported, the most common of which are those involving chromosomes 4, 6,

9, and 19.120 In approximately 5% of cases of acute leukemia in adults, the

ALL1 gene is fused with a portion of itself.121 This special type of gene

fusion is called self-fusion.122 Self-fusion of the ALL1 gene, which is thought

to occur through a somatic recombination mechanism, is found in high incidence

in acute leukemias with trisomy 11 as a sole cytogenetic abnormality. The ALL1

gene encodes a large protein with DNA-binding motifs, a transactivation domain,

and a region with homology to the Drosophila trithorax protein (a regulator of

homeotic gene expression).123,124 The various partners

in ALL1 fusions encode a diverse group of proteins, some of which appear to be

nuclear proteins with DNA-binding motifs.125,126 The ALL1 fusion protein

consists of the aminoterminus of ALL1 and the carboxyl terminus of one of a

variety of fusion partners. It appears that the critical feature in all ALL1

fusions, including self-fusion, is the uncoupling of the ALL1 amino-terminal

domains from the remainder of the ALL1 protein.

Solid tumors, especially sarcomas, sometimes have consistent chromosomal

translocations that correlate with specific histologic types of tumors.127 In

general, translocations in solid tumors result in gene fusions that encode

chimeric oncoproteins. Studies thus far indicate that in sarcomas, the majority

of genes fused by translocations encode transcription factors.128 In myxoid

liposarcomas, the t(12;16)(q13;p11) fuses the FUS (TLS) gene at 16p11 with the

CHOP gene at 12q13.129 The FUS protein contains a transactivation domain that

is contributed to the FUS/CHOP fusion protein. The CHOP protein, which is a

dominant inhibitor of transcription, contributes a protein-binding domain and a

presumptive DNA-binding domain to the fusion. Despite knowledge of these

structural features, the mechanism of action of the FUS/CHOP oncoprotein is not

yet known. In

In DP, an infiltrating skin tumor, both a reciprocal translocation t(17;22)(q22;q13) and supernumerary ring chromosomes derived

from the t(17;22) have been described.

Although early successful studies in this field have been performed with

lymphomas and leukemia, as we have discussed before, the first chromosomal

abnormality in solid tumors to be characterized at the molecular level as a fusion

protein was an inversion of chromosome 10 found in papillary thyroid

carcinomas.132 In this tumor, two main recurrent structural changes have been

described, including inv(10) (q112.2; q21.2), as the

more frequent alteration, and a t(10;17)(q11.2;q23). These two abnormalities

represent the cytogenetic mechanisms which activate the protooncogene ret on

chromosome 10, forming the oncogenes RET/ptc1 and RET/ptc2, respectively.

Alterations of chromosome 1 in the same tumor type have then been associated to

the activation of NTRK1 (chromosome 1), an NGF receptor which, like RET, forms

chimeric fusion oncogenic proteins in papillary thyroid carcinomas.133 A

comparative analysis of the oncogenes originated from the activation of these

two tyrosine kinase receptors has allowed the identification and

characterization of common cytogenetic and molecular mechanisms of their

activation. In all cases, chromosomal rearrangements fuse the tK portion of the

two receptors to the 5′ end of different genes that, due to their general

effect, have been designated as activating genes. In the majority of cases, the

latter belong to the same chromosome where the related receptor is located, 10

for RET and 1 for NTRK1.

Furthermore, although functionally different, the various activating

genes share the following three properties: (1) they are ubiquitously

expressed; (2) they display domains demonstrated or predicted to be able to

form dimers or multimers; (3) they translocate the tK-receptor-associated

enzymatic activity from the membrane to the cytoplasm.

These characteristics can explain the mechanism(s) of oncogenic

activation of ret and NTRK1 protooncogenes. In fact, following the fusion of

their tK domain to activating gene, several things happen: (1) ret and NTRK1,

whose tissue-specific expression is restricted to subsets of neural cells,

become expressed in the epithelial thyroid cells; (2) their dimerization

triggers a constitutive, ligand-independent transautophosphorylation of the

cytoplasmic domains and as a consequence, the latter can recruit SH2 and SH3

containing cytoplasmic effector proteins, such as Shc and Grb2 or phospholipase

C (PLCγ), thus inducing a constitutive mitogenic pathway; (3) the

relocalization in the cytoplasm of ret and NTRK1 enzymatic activity could allow

their interaction with unusual substrates, perhaps modifying their functional

properties.

In conclusion, in PTCs, the oncogenic activation of ret and NTRK1

protooncogenes following chromosomal rearrangements occurring in breakpoint

cluster regions of both protooncogenes could be defined as an ectopic,

constitutive, and topologically abnormal expression of their associated

enzymatic (tK) activity.134top link

Oncogenes in the initiation

and progression of neoplasia

Human neoplasia is a complex multistep process involving sequential

alterations in protooncogenes (activation) and in tumor suppressor genes

(inactivation). Statistical analysis of the age incidence of human solid tumors

indicates that five or six independent mutational events may contribute to

tumor formation.135 In human leukemias, only three or

four mutational events may be necessary, presumably involving different genes.

The study of chemical carcinogenesis in animals provides a foundation for

our understanding the multistep nature of cancer.136 In

the mouse model of skin carcinogenesis, tumor formation involves three phases,

termed initiation, promotion, and progression. Initiation of skin tumors can be

induced by chemical mutagens such as 7,12-dimethyl-benzanthracene

(DMBA) (Figure 6-8). After application of DMBA, the mouse skin appears normal.

If the skin is then continuously treated with a promoter, such as the phorbol

ester TPA, precancerous papillomas will form. Chemical promoters such as TPA

stimulate growth but are not mutagenic substances. Over a period of months of

continuous application of the promoting agent, some of the papillomas will

progress to skin carcinomas. Treatment with DMBA or TPA alone does not cause

skin cancer. Mouse papillomas initiated with DMBA usually have H-ras oncogenes

with a specific mutation in codon 61 of the H-ras gene. The mouse skin tumor

model indicates that initiation of papillomas is the result of mutation of the

H-ras gene in individual skin cells by the chemical mutagen DMBA. For

papillomas to appear on the skin, however, growth of mutated cells must be

continuously stimulated by a promoting agent. Additional unidentified genetic

changes must then occur for papillomas to progress to carcinoma.

Although a single oncogene is sufficient to cause tumor formation by some

rapidly transforming retroviruses such as RSV, transformation by a single

oncogene is not usually seen in experimental models of cancer. Other rapidly

transforming retroviruses carry two different oncogenes that cooperate in

producing the neoplastic phenotype. One well-characterized example of this type

of cooperation is the avian erythroblastosis virus, which carries the erb A and

erb B oncogenes.137 Cooperation between oncogenes can also be demonstrated by

in vitro transformation studies using nonimmortalized cell lines. For example,

studies have shown cooperation between the nuclear myc protein and the

cytoplasmic-membrane-associated ras protein in the transformation of rat embryo

fibroblasts.138 As previously reported, a cooperation between SV40 large T

product and mutated H-ras gene also have been found necessary to transform

normal human epithelial and fibroblast cells provided that they constitutively

expressed the catalytic subunit of telomerase enzyme, indicating a more complex

pattern in the neoplastic conversion of human cells.

Collaboration between two different general categories of oncogenes (eg,

nuclear and cytoplasmic) can often be demonstrated but is not strictly required

for transformation.139 The production of transgenic mice expressing a single

oncogene such as myc has also demonstrated that multiple genetic changes are

necessary for tumor formation. These transgenic mice strains, in fact,

generally show an increased incidence of neoplasia and the tumors that result frequently

are clonal, implying that other events are necessary.The production of

transgenic mice expressing a single oncogene such as myc has also demonstrated

that multiple genetic changes are necessary for tumor formation.140

Cytogenetic studies of the clonal evolution of human hematologic

malignancies have provided much insight into the multiple steps involved in the

initiation and progression of human tumors.141 The

evolution of CML from chronic phase to acute leukemia is characterized by an

accumulation of genetic changes seen in the karyotypes of the evolving

malignant clones. The early chronic phase of CML is defined by the presence of

a single

The initiation and progression of human neoplasia involve the activation

of oncogenes and the inactivation or loss of tumor suppressor genes. The

mechanisms of oncogene activation and the time course of events, however, vary

among different types of tumors. In hematologic malignancies, soft-tissue

sarcomas and the papillary type of thyroid carcinomas, initiation of the

malignant process predominantly involves chromosomal rearrangements that

activate various oncogenes.95 Many of the chromosomal

rearrangements in leukemia and lymphoma are thought to result from errors in

the physiologic process of immunoglobulin or T-cell receptor gene rearrangement

during normal B-cell and T-cell development. Late events in the progression of

hematologic malignancies involve oncogene mutation, mainly of the ras family,

inactivation of tumor suppressor genes such as p53, and sometimes additional

chromosomal translocations.143

In carcinomas such as colon and lung cancer, the initiation of neoplasia

has been shown to involve oncogene and tumor suppressor gene mutations.144

These mutations are generally thought to result from chemical carcinogenesis,

especially in the case of tobacco-related lung cancer, where a novel tumor

suppressor gene (designated FHIT) has been found to be inactivated in the

majority of cancers, particularly in those from smokers.145,146 In

preneoplastic adenomas of the colon, the K-ras gene is often mutated.147

Progression of colon adenomas to invasive carcinoma frequently involves

inactivation or loss of the DCC and p53 tumor suppressor genes (see Figure

6-9). Gene amplification is often seen in the progression of some carcinomas

and other types of tumors. Amplification of the erb B-2 oncogene may be a late

event in the progression of breast cancer.94 Members of the myc oncogene family

are frequently amplified in small-cell carcinoma of the lung.93 As mentioned

previously, amplification of N-myc strongly correlates with the progression and

clinical stage of neuroblastoma.92 Although there is variability in the

pathways of human tumor initiation and progression, studies of various types of

malignancy have clearly confirmed the multistep nature of human cancer.

Summary and conclusions

The initiation and progression of human neoplasia is a multistep process

involving the accumulation of genetic changes in somatic cells. These genetic

changes consist of the activation of cooperating oncogenes and the inactivation

of tumor suppressor genes, which both appear necessary for a complete

neoplastic phenotype. Oncogenes are altered versions of normal cellular genes

called protooncogenes. Protooncogenes are a diverse group of genes involved in

the regulation of cell growth. The functions of protooncogenes include growth

factors, growth factor receptors, signal transducers, transcription factors,

and regulators of programmed cell death. Protooncogenes may be activated by

mutation, chromosomal rearrangement, or gene amplification. Chromosomal

rearrangements that include translocations and inversions can activate

proto-oncogenes by deregulation of their transcription (eg, transcriptional

activation) or by gene fusion. Tumor suppressor genes, which also participate

in the regulation of normal cell growth, are usually inactivated by point

mutations or truncation of their protein sequence coupled with the loss of the

normal allele.

The discovery of oncogenes represented a breakthrough in our

understanding of the molecular and genetic basis of cancer. Oncogenes have also

provided important knowledge concerning the regulation of normal cell

proliferation, differentiation, and programmed cell death. The identification

of oncogene abnormalities has provided tools for the molecular diagnosis and

monitoring of cancer. Most important, oncogenes represent potential targets for

new types of cancer therapies. It is more than a hope that a new generation of

chemotherapeutic agents directed at specific oncogene targets will be

developed. The goal of these new drugs will be to kill cancer cells selectively

while sparing normal cells. One promising approach entails using specific

oncogene targets to trigger programmed cell death. One example of the

accomplishment of such a goal is represented by the inhibition of the

tumor-specific tyrosine kinase bcr/abl in CML by imatinib (Gleevec or

STI571)148(see Figure 6-10). The same compound has been proven active also in a

different tumor type, gastrointestinal stromal tumor, where it inhibits the

tyrosine kinase receptor c-kit.149 Our rapidly

expanding knowledge of the molecular mechanisms of cancer holds great promise

for the development of better combined methods of cancer therapy in the near

future.

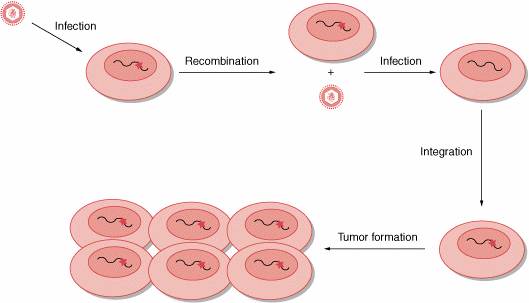

Figure 6-1. Retroviral transduction. A ribonucleic acid (RNA) tumor virus infects a

human cell carrying an activated src gene (red star). After the process

of recombination between retroviral genome and host deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA),

the oncogene c-src is incorporated into the retroviral genome and is

renamed v-src. When the retrovirus carrying v-src infects a human

cell, the viral oncogene is rapidly transcribed and is responsible for the

rapid tumor formation.

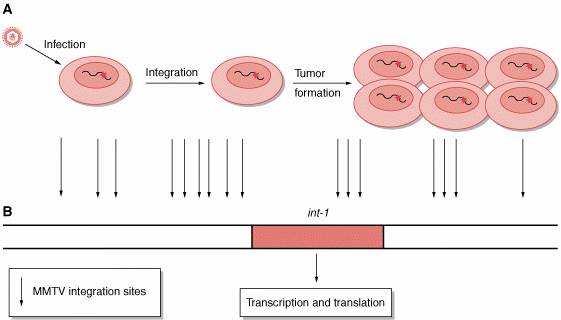

Figure 6-2. Insertional mutagenesis. A, The process is independent of genes carried by the retrovirus.

Retrovirus, for example, mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV), infects a human

cell. The proviral deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) is integrated into the host

genome in infected cells. Rarely, the provirus inserts near a protooncogene

(eg, int-1) and activates the protosoncogene. Activated protooncogene

results in cell transformation and in tumor formation. B, Sites of integration of MMTV retrovirus near the

protooncogene int-1. All sites determine int-1 activation.

Figure 6-3. Transfection assay. Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) from a tumor (eg,

bladder carcinoma) was used to transform a rodent immortalized cell line (NIH

3T3). After serial cycles, DNA from transformed cells was extracted and then

inserted into λ

vector, which was subsequently used to transform an appropriate Escherichia

coli strain. Using a specific probe (ALU), it was possible to

isolate and then characterize the involved human oncogene.

Figure 6-4. Effect of bcl-2 activity

on the control of the cell life. In the presence of BAX only, the cell goes to apoptosis; bcl-2

regulates the cycle of the cell by the interaction with BAX. When bcl-2

is overexpressed, the cell cycle is deregulated and the apoptosis is prevented,

eventually leading to tumor formation. This is an important cause for tumor

formation. PCD = programmed cell death or (apoptosis).

|

Table 6-1. Oncogenes |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Oncogene |

Chromosome |

Method of Identification

|

Neoplasm |

Mechanism of Activation

|

Protein Function |

|

Growth factors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

v-sis |

22q12.3–13.1 |

Sequence homology |

Glioma/fibrosarcoma |

Constitutive production

|

B-chain PDGF |

|

int2 |

11q13 |

Proviral insertion |

Mammary carcinoma |

Constitutive production

|

Member of FGF family |

|

KS3 |

11q13.3 |

DNA transfection |

Kaposi sarcoma |

Constitutive production

|

Member of FGF family |

|

HST |

11q13.3 |

DNA transfection |

Stomach carcinoma |

Constitutive production

|

Member of FGF family |

|

Growth factor receptors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tyrosine kinases: integral membrane

proteins |

|

|

|

|

|

|

EGFR |

7p1.1–1.3 |

DNA amplification |

Squamous cell carcinoma

|

Gene amplification/increased protein |

EGF receptor |

|

v-fms |

5q33–34 (FMS) |

Viral homolog |

Sarcoma |

Constitutive activation

|

CSF1 receptor |

|

v-kit |

4q11–21 (KIT) |

Viral homolog |

Sarcoma |

Constitutive activation

|

Stem-cell factor receptor |

|

v-ros |

6q22 (ROS) |

Viral homolog |

Sarcoma |

Constitutive activation

|

? |

|

MET |

7p31 |

DNA transfection |

MNNG-treated

human osteocarcinoma cell line |

DNA

rearrangement/ligand-independent constitutive activation (fusion proteins) |

HGF/SF receptor |

|

TRK |

1q32–41 |

DNA transfection |

Colon/thyroid carcinomas

|

DNA

rearrangement/ligand-independent constitutive activation (fusion proteins) |

NGF receptor |

|

NEU |

17q11.2–12 |

Point mutation/DNA amplification

|

Neuroblastoma/breast carcinoma

|

Gene amplification |

? |

|

RET |

10q11.2 |

DNA transfection |

Carcinomas

of thyroid; MEN2A, MEN2B |

DNA

rearrangement/point mutation (ligand-independent constitutive

activation/fusion proteins) |

GDNF/NTT/ART/PSP

receptor |

|

Receptors

lacking protein kinase activity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

mas |

6q24–27 |

DNA transfection |

Epidermoid carcinoma |

Rearrangement of 5?

noncoding region |

Angiotensin receptor |

|

Signal transducers |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases |

|

|

|

|

|

|

SRC |

20p12–13 |

Viral homolog |

Colon carcinoma |

Constitutive activation

|

Protein tyrosine kinase |

|

v-yes |

18q21-3 (YES) |

Viral homolog |

Sarcoma |

Constitutive activation

|

Protein tyrosine kinase |

|

v-fgr |

1p36.1–36.2 (FGR) |

Viral homolog |

Sarcoma |

Constitutive activation

|

Protein tyrosine kinase |

|

v-fes |

15q25–26 (FES) |

Viral homolog |

Sarcoma |

Constitutive activation

|

Protein tyrosine kinase |

|

ABL |

9q34.1 |

Chromosome |

CML |

DNA

rearrangement translocation (constitutive activation/fusion proteins) |

Protein tyrosine kinase |

|

Membrane-associated G proteins |

|

|

|

|

|

|

H-RAS |

11p15.5 |

Viral homolog/ DNA transfection

|

Colon, lung, pancreas carcinmoas |

Point mutation |

GTPase |

|

RAS |

12p11.1–12.1 |

Viral homolog/ DNA transfection

|

AML, thyroid carcinoma, melanoma |

Point mutation |

GTPase |

|

N-RAS |

1p11–13 |

DNA transfection |

Carcinoma, melanoma |

Point mutation |

GTPase |

|

gsp |

20 |

DNA sequencing |

Adenomas of thyroid |

Point mutation |

Gs ? |

|

gip |

3 |

DNA sequencing |

Ovary, adrenal carcinoma

|

Point mutation |

Gi ? |

|

GTPase exchange factor (GEF) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dbl |

Xq27 |

DNA transfection |

Diffuse B-cell lymphoma

|

DNA rearrangement |

GEF for |

|

Vav |

19p13.2 |

DNA transfection |

Hematopoietic cells |

DNA rearrangement |

GEF for Ras? |

|

Serine/threonine kinases: cytoplasmic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

v-mos |

8q11 (MOS) |

Viral homolog |

Sarcoma |

Constitutive activation

|

Protein kinase (ser/thr) |

|

v-raf |

3p25 (RAF-1) |

Viral homolog |

Sarcoma |

Constitutive activation

|

Protein kinase (ser/thr) |

|

pim-1 |

6p21 (PIM-). |

Insertional mutagenesis

|

T-cell lymphoma |

Constitutive activation

|

Protein kinase (ser/thr) |

|

Cytoplasmic regulators |

|

|

|

|

|

|

v-crk |

17p13 (CRK) |

Viral homolog |

|

Constitutive

tyrosine phosphorilation of cellular substrates (eg, paxillin) |

SH-2/SH-3 adaptor |

|

Trancription Factors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

v-myc |

8q24.1 (MYC) |

Viral homolog |

Carcinoma, myelocytomatosis

|

Deregulated activity |

Transcription factor |

|

N-MYC |

2p24 |

DNA amplification |

Neuroblastoma; lung carcinoma

|

Deregulated activity |

Transcription factor |

|

L-MYC |

1p32 |

DNA amplification |

Carcinoma of lung |

Deregulated activity |

Transcription factor |

|

v-myb |

6q22–24 |

Viral homolog |

Myeloblastosis |

Deregulated activity |

Transcription factor |

|

v-fos |

14q21–22 |

Viral homolog |

Osteosarcoma |

Deregulated activity |

Transcription factor API |

|

v-jun |

p31–32 |

Viral homolog |

Sarcoma |

Deregulated activity |

Transcription factor API |

|

v-ski |

1q22–24 |

Viral homolog |

Carcinoma |

Deregulated activity |

Transcription factor |

|

v-rel |

2p12–14 |

Viral homolog |

Lymphatic leukemia |

Deregulated activity |

Mutant NFKB |

|

v-ets-1 |

11p23–q24 |

Viral homolog |

Erythroblastosis |

Deregulated activity |

Transcription factor |

|

v-ets-2 |

21q24.3 |

Viral homolog |

Erythroblastosis |

Deregulated activity |

Transcription factor |

|

v-erbA1 |

17p11–21 |

Viral homolog |

Erythroblastosis |

Deregulated activity |

T3 Transcription factor |

|

v-erbA2 |

3p22–24.1 |

Viral homolog |

Erythroblastosis |

Deregulated activity |

T3 Transcription factor |

|

Others |

|

|

|

|

|

|

BCL2 |

18q21.3 |

Chromosomal translocation

|

B-cell lymphomas |

Constitutive activity

|

Antiapoptotic protein |

|

MDM2 |

12q14 |

DNA amplification |

Sarcomas |

Gene amplification/increased protein |

Complexes with p53 |

AML =

acute myeloid leukemia; CML = chronic myelogenous leukemia; CSF = colony

stimulating factor; DNA = deoxyribonucleic acid; EGF = epidermal growth factor;

FGF = fibroblast growth factor; GTPase = guanosine triphosphatase; HGF =

hepatocyte growth factor; NGF = nerve growth factor; PDGF = platelet-derived

growth factor.

Figure 6-5. Schematic representation of the

main mechanisms of oncogene activation (from protooncogenes to oncogenes). The normal gene (protooncogene) is depicted with

its transcibed portion (rectangle). In the case of gene amplification, the

latter can be duplicated 100-fold, resulting in an excess of normal protein. A

similar situation can occur when following chromosome rearrangements such as

translocation, the transcription of the gene is now regulated by novel

regulatory sequences belonging to another gene. In the case of point mutation,

single aminoacid substitutions can alter the biochemical properties of the gene

product, causing, in the example, its constitutive enzymatic activation.

Chromosome rearrangements, such as translocation and inversion, can then

generate fusion transcripts resulting in chimeric oncogenic proteins.

Figure 6-6. C-myc translocations found

in Burkitt lymphoma. A, t(8;14)(q24;q32)

translocation involving the locus of immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene located at

14q32. B, t(8;14)(q24;q32) translocation where only 2 exons (Ex) of c-myc

are translocated under regulatory elements from the immunoglobulin heavy-chain

locus located at 14q32. C, t(8;22)(q24;q11) translocation involving the l

locus of immunoglobulin light-chain gene at 22q11. D, t(2;8)(p12;q24)

translocation involving the κ locus of immunoglobulin light-chain gene located at 2p12.

Figure 6-7. Gene fusion. The t(9;22)(q34;q11) translocation in chronic

myelogenous leukemia (CML) determines the fusion of the c-abl gene with

the bcr gene. Such a gene fusion encodes an oncogenic chimeric protein

of 210 kDa. Chr = chromosome.

|

Table 6-2. Oncogene Amplification in Human

Cancers |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

Tumor

Type |

Gene

Amplified |

Percentage |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

Neuroblastoma |

MYCN |

20–25 |

|

|

Small-cell

lung cancer |

MYC |

15–20 |

|

|

Glioblastoma |

ERB

B-1 (EGFR) |

33–50 |

|

|

Breast

cancer |

MYC |

20 |

|

|

|

ERB

B-2 (EGFR2) |

~20 |

|

|

|

FGFR1 |

12 |

|

|

|

FGFR2 |

12 |

|

|

|

CCND1 (cyclin D1) |

15–20 |

|

|

Esophageal

cancer |

MYC |

38 |

|

|

|

CCND1 (cyclin D1) |

25 |

|

|

Gastric

cancer |

K-RAS |

10 |

|

|

|

CCNE (cyclin E) |

15 |

|

|

Hepatocellular

cancer |

CCND1 (cyclin D1) |

13 |

|

|

Sarcoma |

MDM2 |

10–30 |

|

|

|

CDK4 |

11 |

|

|

Cervical

cancer |

MYC |

25–50 |

|

|

Ovarian

cancer |

MYC |

20–30 |

|

|

|

ERB

B-2 (EGFR2) |

15–30 |

|

|

|

AKT2 |

12 |

|

|

Head

and neck cancer |

MYC |

7–10 |

|

|

|

ERB

B-1(EGFR) |

10 |

|

|

|

CCND1(cyclin D1) |

~50 |

|

|

Colorectal

cancer |

MYB |

15–20 |

|

|

|

H-RAS |

29 |

|

|

|

K-RAS |

22 |

|

|

Table

6-3. Neuroblastoma |

||

|

Benign

ganglioneuromas |

0/64(0%) |

100 |

|

Low

stages |

31/772 (4%) |

90 |

|

Stage

4-S |

15/190 (8%) |

80 |

|

Advanced

stages |

612/1.974 (31%) |

30 |

|

Total |

658/3000 (22%) |

50 |

MYCN copy numbers are correlated with stage and

survival in neuroblastoma.

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rearrangements |

Disease |

Protein

Type |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

c-ABL (9q34) |

t(9:22)

(q34:q11) |

CML and

acute leukemia |

Tyrosine kinase activated by BCR |

|

BCR (22q11) |

|

|

|

|

PBX-1(1q23) |

t(1:19)(q23:p13.3) |

Acute pre-B-cell leukemia |

Homeodomain |

|

E2A(19p13.3). |

HLH |

|

|

|

PML(15q21) |

t(15:17)

(q21:q11–22) |

Acute

myeloid leukemia |

Zinc

finger |

|

RAR(17q21) |

|

|

|

|

CAN(6p23) |

t(6:9)

(p23:q34) |

Acute

myeloid leukemia |

No

homology |

|

DEK(9q34). |

|

|

|

|

REL |

ins(2:12) (p13:p11.2–14) |

Non-Hodgkin

lymphoma |

NF(?)B family |

|

NRG |

|

|

No

homology |

|

Oncogenes

juxtaposed with IG loci |

|||

|

c-MYC |

t(8:14)

(q24:q32) |

Burkitt

lymphoma; BL-ALL |

HLH

domain |

|

|

t(2:8)

(p12:q24) |

|

|

|

|

t(8:22)

(q24:q11) |

|

|

|

BCL1

(PRADI?) |

t(11:14)

(q13:q32) |

B-cell chronic lymphocyte leukemia |

PRADI-GI

cyclin |

|

BCL-2 |

t(14:18)

(q32:21) |

Follicular

lymphoma |

Inner

mitochondrial membrane |

|

BCL-3 |

t(14:19)

(q32:q13.1) |

Chronic

B-cell leukemia |

CDC10

motif |

|

IL-3 |

t(5:14)

(q31:q32) |

Acute pre-B-cell leukemia |

Growth

factor |

|

Oncogenes juxtaposed with TCR loci |

|||

|

c-MYC |

t(8:14)

(q24:q11) |

Acute

T-cell leukemia |

HLH

domain |

|

LYLA |

t(7:19)

(q35:p13) |

Acute

T-cell leukemia |

HLH

domain |

|

TALA/SCL/TCL-5 |

t(1:14)

(q32:q11) |

Acute

T-cell leukemia |

HLH domain |

|

TAL-2 |

t(7:9)

(q35:q34) |

Acute

T-cell leukemia |

HLH

domain |

|

Rhombotin

1/Ttg-1 |

t(11:14)

(p15:q11) |

Acute

T-cell leukemia |

LIM

domain |

|

Rhombotin

2/Ttg-2 |

t(11:14)

(p13:q11) |

Acute

T-cell leukemia |

LIM

domain |

|

|

t(7:11)

(q35:p13) |

|

|

|

HOX 11 |

t(10:14)

(q24:q11) |

Acute

T-cell leukemia |

Homeodomain |

|

|

t(7:10)

(q35:q24) |

|

|

|

TAN-1 |

t(7:9)

(q34:q34.3) |

Acute

T-cell leukemia |

Notch

homologue |

|

TCL-1 |

t(7q35-14q32.1) |

B-cell chronic lymphocitic leukemia |

|

|

|

or inv |

|

|

|

|

t(14q11-14q32.1) |

|

|

|

|

or inv |

|

|

|

Solid

Tumors |

|

|

|

|

Gene fusions in sarcomas |

|

||

|

FLI1,EWS |

t(11:22)

(q24:q12) |

Ewing sarcoma |

Ets

transcription factor family |

|

ERG,EWS |

t(21:22)

(q22:q12) |

Ewing sarcoma |

Ets

transcription factor family |

|

ATV1,EWS |

t(7:21)

(q22:q12) |

Ewing sarcoma |

Ets

transcription factor family |

|

ATF1,EWS |

t(12:22)

(q13:q12) |

Soft-tissue clear cell sarcoma |

Transcription

factor |

|

CHN,EWS |

t(9:22)

(q22 31:q12) |

Myxoid chondrosarcoma |

Steroid

receptor family |

|

WT1,EWS |

t(11:22)

(p13:q12) |

Desmoplastic small round cell tumor |

Wilms

tumor gene |

|

SSX1,SSX2,SYT |

t(X:18) (p11.2:q11.2) |

Synovial

sarcoma HLH domain |

|

|

PAX3,FKHR |

t(2:13)

(q37:q14) |

Alveolar

rhabdomysarcoma |

Homeobox

homologue |

|

PAX7,FKHR |

t(1:13)

(q36:q14) |

Rhabdomyosarcoma |

Homeobox

homologue |

|

CHOP,TLS |

t(12:16)

(q13:p11) |

Myxoid liposarcoma |

Transcription

factor |

|

var,HMG1-C |

t(var:12) (var:q13–15) |

Lipomas |

HMG

DNA-binding protein |

|

HMG1-C?

|

t(12:14)

(q13–15) |

Leiomyomas |

HMG

DNA-binding protein |

|

Gene

fusions in thyroid carcinomas |

|||

|

RET/ptc1 |

inv(10) (q11.2:q2.1) |

Papillary

thyroid carcinomas |

Tyrosine kinase actived by H4 |

|

RET/ptc2 |

t(10:17)

(q11.2:q23) |

Papillary

thyroid carcinomas |

Tyrosine kinase actived by RIa(PKA) |

|

RET/ptc3 |

inv(10) (q11.2) |

Papillary

thyroid carcinomas |

Tyrosine kinase actived by ELE1 |

|

TRK |

inv(1) (q31:q22–23) |

Papillary

thyroid carcinomas |

Tyrosine kinase actived by TPM3 |

|

TRK-T1(T2) |

inv(1) (q31:q25) |

Papillary

thyroid carcinomas |

Tyrosine kinase actived by TPR |

|

TRK -T3 |

t(1q31:3) |

Papillary

thyroid carcinomas |

Tyrosine kinase actived by TFG |

|

Haematopoietic

and solid tumors |

|||

|

Oncogenes

juxtaposed with other loci |

|||

|

PTH deregulates PRAD1 |

inv(11)(p15:q13) |

Parathyroid

adenoma |

PRADI-GI

cyclin |

|

BTG1

deregulates MYC |

t(8:12)(q24:q22) |

B-cell

chronic lymphocytic |

MYC-HLH

domain |

HLH = helix loop helix

structural domain; HMG = high mobility group; H4; ELE1; IG = immunoglobulin;

TPR and TFG = partially uncharacterized genes with a dimerizing coiled-coil

domain; RIa = regulatory subunit of PKA enzyme; TCR =

T-cell receptor; TPM3 = isoform of nonmuscle tropomyosin.

Figure 6-8. A model of exposure to a mutagen and to a tumor

promoter. Cancer develops

exclusively when the exposure to promoter follows the exposure to carcinogen

(mutagen; eg, 7,12-dimethyl-benzanthracene [DMBA]) and

only when the intensity of the exposure to promoter is higher than a threshold.

Figure 6-9. Colorectal cancer development. Colorectal cancer results from a series of

pathologic changes that transform normal colonic epithelium into invasive

carcinoma. Specific genetic events, shown by vertical arrows, accompany this

multistep process.

Figure 6-10. Mode of action of STI571. The effect of ATP binding on the oncoprotein

BCR-ABL (left): the fusion protein binds the molecule of ATP in the kinase

pocket. Afterwards, it can phosphorylate a substrate, that

can interact with the downstream effector molecules. When STI571 is present

(right), the oncoprotein binds STI571 in the kinase pocket (competing with

ATP); therefore the substrate cannot be phosphorylated.

Figure 6-11. Paracrine and autocrine stimulation. A, A growth factor produced by the cell on the right stimulates another

cell carrying the appropriate receptor (left) on cell membrane. This process is

named paracrine stimulation. B, A growth factor is produced by the same cell expressing the

corresponding receptor. This process is designated autocrine stimulation.

Figure 6-12. Representative examples of tyrosine kinase receptor

families. EGF = epidermal growth

factor; FGF = fibroblast growth factor; Ig= immunoglobulin; IGF1 = insulinlike

growth factor; PDGF = platelet-derived growth factor; VEGF = vascular

endothelial growth factor.